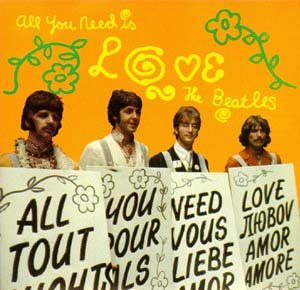

I don’t want to be one of those people that blames the Baby Boomers for everything. I look at my own parents and find it hard to believe there aren’t great Boomers out there producing, working hard, and carrying on the valuable vestiges of the Greatest Generation. But one of the more irritating facets of this generation is this radical sense of idealism that leads to paramount levels of impatience. Though Gens X and Y clearly do not share this idealism (it seems to have been replaced by cynicism if not outright pessimism), the impatience passed down by Boomers has officially been diagnosed as ADD/ADHD/etc. The theme song of for the Boomers teenage years, “All You Need is Love” turned out to be a daydream, a fanciful notion that never quite panned out as planned. Just ask The Beatles.

I don’t want to be one of those people that blames the Baby Boomers for everything. I look at my own parents and find it hard to believe there aren’t great Boomers out there producing, working hard, and carrying on the valuable vestiges of the Greatest Generation. But one of the more irritating facets of this generation is this radical sense of idealism that leads to paramount levels of impatience. Though Gens X and Y clearly do not share this idealism (it seems to have been replaced by cynicism if not outright pessimism), the impatience passed down by Boomers has officially been diagnosed as ADD/ADHD/etc. The theme song of for the Boomers teenage years, “All You Need is Love” turned out to be a daydream, a fanciful notion that never quite panned out as planned. Just ask The Beatles. To function successfully in the world, we need more than love, or we at least need love properly understood. Often, I find that when those in my generation speak of love, they have either learned to cling to their parent’s (or the culture’s) romantic notions of love, or have rejected it wholeheartedly. But love is an enterprise in sacrifice more than the living out of a gut feeling. The problem with gut feelings, or the kind of love the pop artists tend to sing about, is that gut feelings change as do life circumstances. It strikes me that if The Beatles were singing about love as sacrifice, love as joy, or about love adapting and evolving to life’s curveballs, they would have been dead-on.

But I’m not sure the Boomers took it that way. This was their time, they were the generation that was going to prove their parents’ Depression-era advice wrong, they were finally going to have their cake and eat it too. All they needed was love. If they could just corral their good intentions into some sort of policy, we could finally achieve the utopia that we have been on the verge of achieving for centuries, but could never quite make it. The Boomers would achieve what so many other generations couldn’t.

This sort of daydreaming led to scores of failed policies from conception to implementation. The easiest examples are the economic policies that actually helped the pre-welfare poor were scrapped in favor of massive spending that made the problem worse. The unintended consequences of government growth and/or action were never thoughtfully considered by the Boomers and their legislators. I’m no foreign policy expert, but a continued weakness in how we wage/win war is, I think, a byproduct of this idealism run amok. War, at best, is a necessary evil, and daydreaming about it leads to second-guessing that only makes the problem worse.

But secular society isn’t the only place this motto has been adopted. I find my own church body (and similar church bodies) operating within this idealistic model, which, of course, in many ways is true. The Bible is clearly full of endorsements of love: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son,” from St. John or “But now abide in faith, hope, love, these three; and the greatest of these is love” from St. Paul. (These are the “greatest hits” of bible verses on love, and for good reason.) But when scripture speaks of love, I find that it can be a different understanding from what even the church calls love.

A recent television advertisement (is this what evangelism has become?) by the United Church of Christ (UCC) utilizes the slogan, “Jesus didn’t turn people away. Neither do we,” implying that the key feature of the UCC is that it is welcoming of all people, just as Jesus was. Whatever your lifestyle, we welcome you. Other mainline churches have similar advertising slogans, making sure the general non-churchgoing public knows that they are welcome. Fine, but is that all the Church is about? It seems that beneath all of this is the mantra, “All you need is love.” What about the law? What about virtue? What about living out our faith? What about sacrifice, carrying the cross, all that good stuff?

It’s probably not a good career move for me to seemingly place myself at odds with Jesus, which I don’t see myself doing at all. But I’ve found if you criticize the love-only model of the faith, you’re quickly labeled a legalist. I just want to accurately define what we mean by grace and love, not only within our personal relationships, but also our sacred and even secular institutions. The idealism of needing love and love alone has gotten us into trouble, not because the intentions were bad, but because the warmest, fuzziest blanket statement “All you need is love” is just too good to let go when the policy proves a failure. Give me two people who merely like each other but agree in principle as to what marriage is about and I would wager there marriage would be more successful than a couple wildly in love who has immature views of marriage. The same is true for a moral society. It’s great that we should all love each other. But how do we live together in the meantime?

No comments:

Post a Comment