I'm fortunate to live in a town that can claim to have a historic 'downtown' in the form of a courthouse square. Our county courthouse is dressed in a refined art-deco style, framed by streets lined with facades most of which are more than 90 years old or so. There are a couple of retailers, antiques and cafes. Since pedestrian traffic is almost non-existent in this part of town, most of the space within the buildings framing the square has been leased as professional offices such as law firms and dentists as well as housing municipal and county services. Compared to other suburban communities in the Dallas Metroplex that resemble each other and is almost impossible to locate its core, my town possesses an authentic sense of place with the courthouse and a handful of surrounding streets containing old Victorian cottages.

I'm fortunate to live in a town that can claim to have a historic 'downtown' in the form of a courthouse square. Our county courthouse is dressed in a refined art-deco style, framed by streets lined with facades most of which are more than 90 years old or so. There are a couple of retailers, antiques and cafes. Since pedestrian traffic is almost non-existent in this part of town, most of the space within the buildings framing the square has been leased as professional offices such as law firms and dentists as well as housing municipal and county services. Compared to other suburban communities in the Dallas Metroplex that resemble each other and is almost impossible to locate its core, my town possesses an authentic sense of place with the courthouse and a handful of surrounding streets containing old Victorian cottages.For several years I worked for an architecture firm that specializes in historic preservation. What mostly kept us busy was an endless pipeline of historic courthouses that could afford to be renovated thanks to a program pushed by that governor who was known to be such a friend to architects, George W. Bush (???!!!). Texas has over two hundred counties, and many of them contain beautiful courthouses that span in from Richardsonian Romanesque to Second Empire to Neo-Classical, to Art-Deco. Although I've always had a soft-spot for historic architecture, I realized in that job that I wanted to create rather than restore someone else's work. But even with all that knowledge and insight I gained from this job, there is one thing I never got around to doing: I have never actually visited the historic square in my town.

I've driven through it from time to time, mostly on my way to places near the square. But I never walked past the storefronts, nor even spent an afternoon at the few arts and crafts fair held on the lawn around the courthouse. I've always told myself that I will get around to making a quick trip to the square but so far, I've had no good reason to do so.

I've driven through it from time to time, mostly on my way to places near the square. But I never walked past the storefronts, nor even spent an afternoon at the few arts and crafts fair held on the lawn around the courthouse. I've always told myself that I will get around to making a quick trip to the square but so far, I've had no good reason to do so.In college I did not own a car, and thus I was relegated to walking to the courthouse square of the town to accomplish the most basic errands. My experience made me aware of how stagnant these places were, how difficult it was to get the most basic things (for example there was a drug store which only would sell Tom's brand toothpaste, when all I really wanted was Crest). The quality of the services were not better in inverse proportion to all the convenience of chain stores. The square during my college years was in relatively healthy shape, with several restaurants, a soda fountain, an independently-owned coffee house, a small department store, a bank and even a hardware store. And yet there was nothing that compelled me to want to return to the square other than that I couldn't drive to the town's outskirts near the main highway to frequent the big-box retailers.

What will make me come to these architecturally handsome urban places on a regular basis? In one word: anchors. This term is more commonly used in the realm of real-estate development, which describes a any kind of major attraction, whether a major store or a non-profit leisure destination (such as zoos, museums, municipal water-parks, performance halls, school campus) that can generate a high volume of pedestrian traffic from which smaller nearby enterprises can benefit. The problem with a lot of town squares is that they have no real anchors to draw people. A government office building or any other non-retail business will not generate enough foot traffic to supply a rich variety of services and stores. That's why across the street from the courthouse there might be one or two delis and none more, since that is all the demand from the workers in the vicinity can muster. The equation changes considerably when the anchor functions as an irresistible magnet for people. This is usually achieved when an establishment offers a diversion unavailable at a relatively close distance elsewhere.

People will always want to enjoy themselves by going somewhere. Catching a movie, watching theatrical performance, or even observing captive wild animals is something people do repeatedly for fun. But in this day and age of extraordinary material wealth, most people spend their time outside work or home at stores and restaurants. We especially like to visit with greater frequency stores with lots of selection, ever-changing inventory and efficient service. One doesn't find these amenities in historic town squares. The beauty of the architecture doesn't breath life to a space; it requires the engine of commerce powered by the motor of an anchor.

Chain stores serve the anchoring purpose well and are extremely prized by municipalities who crave the sales tax revenue. They tend to occupy new structures that generally charge higher rents, and because of the strength of their brand can generate lots of revenue quickly compared to mom-and-pop stores. As chains, they are by nature not original to the place in which they are located, but rather makes them serve as reminders of the world outside the community, with all of its universality, its sameness and standardization and alien-ness to local color. It is precisely these attributes that appeal to most town residents. Chains offer an expansive selection of goods that keep local residents from having to leave town to find them, meaning there is a greater likelihood for chance encounters with fellow towns folk. Chains command brand loyalty, guaranteeing that people will return much more frequently than the half-dozen or less times townspeople convene at the historic square or street block. It is therefore not very surprising to find the most bustling area of town to be right at the intersection of a major state road and the interstate highway. Every major big-box retailer and chain restaurant under the sun seems to be represented, and the parking lot is streaming with pedestrians.

Chain stores serve the anchoring purpose well and are extremely prized by municipalities who crave the sales tax revenue. They tend to occupy new structures that generally charge higher rents, and because of the strength of their brand can generate lots of revenue quickly compared to mom-and-pop stores. As chains, they are by nature not original to the place in which they are located, but rather makes them serve as reminders of the world outside the community, with all of its universality, its sameness and standardization and alien-ness to local color. It is precisely these attributes that appeal to most town residents. Chains offer an expansive selection of goods that keep local residents from having to leave town to find them, meaning there is a greater likelihood for chance encounters with fellow towns folk. Chains command brand loyalty, guaranteeing that people will return much more frequently than the half-dozen or less times townspeople convene at the historic square or street block. It is therefore not very surprising to find the most bustling area of town to be right at the intersection of a major state road and the interstate highway. Every major big-box retailer and chain restaurant under the sun seems to be represented, and the parking lot is streaming with pedestrians.Although the town in which I live can't compare to the cache and urban richness of the country's greatest cities, it is nonetheless quite fascinating to monitor its growth at the local level. Each time I drive by familiar streets I notice a new structure emerging out of nowhere or a grand opening to a new business being advertised. There is lots of local excitement around the arrival of a major chain store, as if it gives the town some much-needed stature. One of my favorite chain restaurants just opened last weekend, "La Madeleine", which now gives our town instant credibility among other rival towns in the area. I realize that such enthusiasm for this or that chain may sound shallow and devalue the historic heritage of our small towns. Yet the reason the arrival of chains to the town generates so much interest is that their existence is a testament to our town becoming more livable.

Dallas' very own Virginia Postrel writes about this particular feature of retail chains that have come to dominate the American landscape. She argues that while chain stores have sapped the uniqueness of towns, they have made them more livable and its citizens better off overall. Although tourists remark than traveling from one city to the next has lost its allure due to the homogeneous commercial landscape brought on by chain stores, these towns in essence function to serve the needs of their inhabitants, and in particular their needs as consumers. Although having elegant landmarks add distinctiveness to the town's image and attracts outside visitors, they do not help retain a town's population nor attract newcomers. Postrel summarizes well why cities should exist for livability than for historic charm:

Contrary to the rhetoric of bored cosmopolites, most cities don’t exist primarily to please tourists. The children toddling through the Chandler mall hugging their soft Build-A-Bear animals are no less delighted because kids can also build a bear in Memphis or St. Louis. For them, this isn’t tourism; it’s life—the experiences that create the memories from which the meaning of a place arises over time.

I'm not arguing that chain stores are the answer reviving the historic town centers across the country. Rather, I think city leaders and planners have to consider ways to draw in repeat customers; that is, townspeople who satisfy their wants and needs within city limits. Whether that is done by more institutional anchors or more commercial ones, a constant and diverse flow of traffic is crucial. Successfully achieving this first goal enables more fruitful re-developments to follow. Once this generator of pedestrian traffic is retained, it is fundamental that city leaders preserve the conditions helpful to the success of that anchor. To implement policies cracking down on anchors just because they are not authentic to the town will kill town centers much quicker than the time it took to lure them in. It is just as critical that towns should diversify businesses and multiply the number of anchors to cope with the fluctuating nature of business activity.

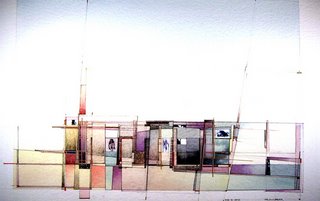

Looking at my town's masterplan for its historic core, I see little to no evidence that a strategy to lure a major anchor of a sort has been articulated. Indeed, the proposed building typologies are quite attractive, and will likely add charm to our town's image that even its residents will find appealing. But just to write that certain blocks or parts of buildings will accommodate desirable restaurants and cafes does not mean that they will come by virtue of the attractive street-scapes described in the masterplan. Certain ideas, like that of inserting a clock tower and a band-shell on the grounds surrounding the courthouse, while potentially achieving a sense of place by providing an attractive backdrop to festivals, will do little to contribute to regular pedestrian traffic. My impression from having worked on a few of these masterplans is that they intend not to re-energize the historic core of the town as a central economic engine, but to turn them into glorified living museums that are mildly commercially sustainable. They admirably find new uses for the old urban fabric, but they don't restore these places to nearly the level of prominence they once played in the lives of townspeople. They become forever consigned as just another leisurely distraction that you may take out-of town guests over to see, but nothing remotely as important as the local strip shopping center.

Ironically enough, my town is investing lots of its own resources to build a brand new town-center along its waterfront, far from its historic town square. Why do our city leaders think this a good idea? For one thing, the new town center, while looking and feeling like a traditional urban street, is more optimally planned for accommodating major commercial anchors. There is a cinema complex at one end of the development and a brand new hotel/conference center at the opposite end, with "blocks" of retail, chain restaurants with views of the lake, and elegant fountains and walkways. There's even a landscaped amphitheater for open-air concerts, and the new town center has recently proved to be effective in gathering large numbers of people to watch fireworks.

Such "lifestyle centers" are growing in popularity in suburbs across the country. They are basically unenclosed shopping malls, and their thematic architecture makes little attempt to relate the authentic vernacular of historical areas of the towns near which they are located. Our new instant town center by the lake resembles an Italian fishing village with cardboard cutout detailing, instead of the much more native Texas lakehouse style found in nearby rural areas. Still, they manage to restore a sense of place, regardless of how instantaneously they are conceived. Our older, and often more tastefully built town centers of yore could apply lessons from the success of lifestyle centers.

Maybe then I'll actually patronize the businesses of the local town square.